One half of AnVRopomotron used photogrammetric scans that others have made, but the Scale Model Hall half is mostly my own creation. When I was just getting started with A-Frame, I experimented with building models just from primitive shapes, but concluded that learning low-poly style modeling was an attainable and more rewarding method. I modeled a gorilla after giving up on a chimpanzee. The gorilla worked out because it had larger shapes than the details of a chimpanzee’s anatomy. By chance the gorilla is also the largest living primate, which made it an interesting subject of comparison in a scale-based VR setting. I made the first final draft of the gorilla and moved from there.

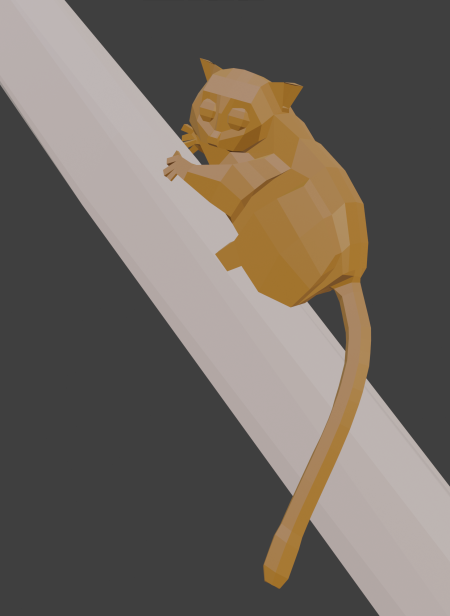

{ Gorilla v2 (added big toes and re-colored) and mouse lemur to show extremes in modern primate size. }

My second model was the mouse lemur, the world’s smallest living primate. I followed the same tutorial to get started using a mashup of photo references from the front and side. The mouse lemur has more defined eyes and digits than the gorilla so I worked those out by using the knife tool to make new edges and pushing them into the right shapes. As with the gorilla’s head, I rendered the hands separately before moving them into place. I made one hand, mirrored a duplicate, and moved the fingers into different positions before attaching it to the other wrist. To put the small primate at eye level, I quickly made a simple branch structure out of distorted cylinders that the lemur could sit on.Â

Continuing the biggest-smallest theme, my next model was the Gigantopithecus, the largest known primate ever. The new challenge this time was that there were not clear photo references. Since this prehistoric ape is only known from individual bones and teeth, there were many reconstructions but no clear front or side views. The benefit of this situation is that I could make my own version of this animal. One detail of Gigantopithecus reconstructions, especially sculptures, is that they are shown comfortably standing on their legs. Based on living great apes, Gigantopithecus would have been just as awkward standing upright as a gorilla or orangutan. I wanted to model my Gigantopithecus standing up as well, since the size is more impressive, but in a more realistic way. I used photos of orangutans standing on two legs as my reference since Gigantopithecus was a fellow Asian great ape. What the photos show is that orangutans often support themselves with their arms, such as by reaching up to a support. Since that further accentuates the height of the shape, I used that in my model. I debated whether to include orangutan face flaps or not. I settled on modeling them using the general rule that fossils are modeled based on the closest living relative.

The next sculpt was a combination past and present. I wanted to make the smallest known primate, Eosimias, but there is even less known about its appearance than Gigantopithecus. As a basal anthropoid, some where before the split of the monkey, ape, and human lineages. Based on its location in the primate family tree, the best guess is that it was a tiny generic monkey. Instead of modeling a generic monkey from scratch, I modeled a rhesus monkey first, then scaled it down and added more arboreal traits like a long tail to make the Eosimias. I placed it on the highest finger of the Gigantopithecus to really show off the variation in primate sizes. It’s basically invisible unless if you know where to look, but the info window for that display mentions the tiny primate. Its place in the room was temporary, though.

Part of the reference-finding process is referring to scientific descriptions of the anatomy, especially for extinct species. While looking at Eosimias research, I noticed that the oft-repeated fact that it was “thumb-sized†does not actually show up in the peer-reviewed literature. The comparison is also unclear as used in other media since human thumbs are different sizes and different sources disagree on whether the primate is compared to a thumb’s length or width. The research papers also never said it was the smallest known primate, and actually said it was roughly mouse lemur sized. Looking for what is actually considered an undisputed smallest known primate was a challenge. The current level of research points towards Archicebus as the title-holder, just a little smaller than the mouse lemur. I remade my Eosimias model to conform to Archicebus measurements, such as eye orbit and hand size. Unfortunately Eosimias no longer had a place in the site.Â

I felt that I needed practice in 3D modeling to lead up to the next model: modern Homo sapiens. Humans have especially complex shapes in biology and clothing (I was certainly not ready to model a nude human). A new detail to consider is who should be the ‘representative’ of our species in AnVRopomotron. Our species is very diverse in physical appearance across spectrums of sex, skin color, and silhouette. Any choice would be unrepresentative of many of us at some level. I settled on Jane Goodall since she is a primatologist who contributed greatly to anthropology and to conservation. There are also good photo references of her from many angles. I modeled her in a walking and talking pose with hands entwined in front for comparison with the other models. She’s also rendered clothed in her field outfit, which fortunately had simple shapes with only a few complexities such as pant cuffs and a collared top. The original model color is the beige from her clothes so it is skin color agnostic. I later changed the color, as detailed below, but still kept it far from representing a human skin color.

The Gigantopithecus, Archicebus, and modern Homo sapiens were part of the centerpiece of the app. The last model for the first thing the user sees is Lucy, the famous Australopithecus. Rendering the human model made Lucy much easier, taking only days instead of weeks to get a usable sculpt. I thought of shaping a copy of the human model to Lucy, but decided that I could start from scratch even faster. By this time I start with a lot of the limbs separate to be joined later. This allows for a lot of posing without deforming the attached polygons. The separate parts were the head, neck, torso, upper and lower arms, upper and lower legs, and each hand and foot. There were ample photo references available for Lucy specifically and australopithecines in general. I debated the pose for a while. Most reconstructions are of her walking or standing still (with special mention for the twisted contrapposto figure in Australopithecus and Kin {Ward and Hammond, 2016}. One thing I see in a lot of descriptions that I disagree with is the abundance of human features in Lucy, especially her face. Based on just the skeleton, Lucy’s head was ape-like instead of human-like so she would have been closer to chimps in expression and mannerisms. My idea was to give her chimpanzee expressions, but ones that humans could relate to. I referred to the Great Ape Dictionary website, which has a video database of chimpanzee gestures. I chose the reach-palm gesture for Lucy to be welcoming to the user and to show off her long arms. With one arm extended out, the model looked extremely off balance. Her other arm had to pull back to be a counterweight, along with turning the body. The result shows a plausible way for a primate with those proportions to pose.Â

The centerpiece went through several changes before the final final version. At first, they were all flat shaded with representative colors. When I started to color the other models, such as the gorilla and mouse lemur, with more detail, I hesitated to do the same for the centerpiece. The main reason was that I really did not want the human figure to have a realistic skin color (unfortunately a case of no one gets represented so everyone is equal). A solution I settled on was to take the centerpiece towards a stylistic direction. I recolored all of the models to the same bronzy shade and use Blender’s materials to make it shine like polished metal. This made the centerpiece look like its own finished piece instead of a rough version of the other models.Â

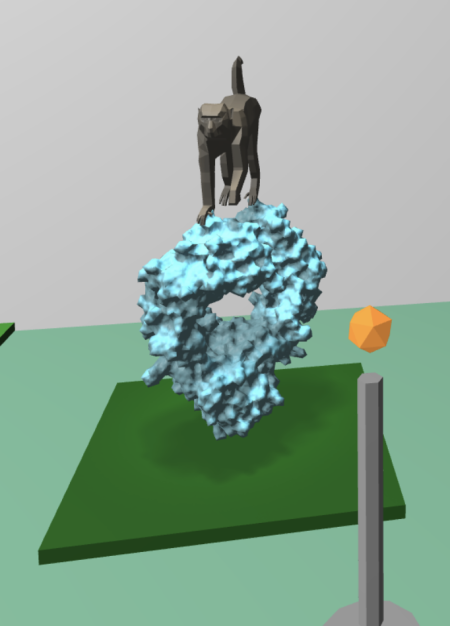

I then returned to the rhesus monkey. I wanted something to prop up the model to human height so it was more visible. I was going make a quick rock, but a chance comment from my brother (“are you going to model microscopic things?â€) inspired me to find something more creative. Looking at protein databases online led to a usable model of the antibody that fights the Rhesus factor in human blood. I expanded that model to be a meter tall and perched the monkey on top of it, adjusting its hands and feet to contact the protein model.Â

{ Rhesus macaque and anti-Rh antibody v1. Shading of the antibody is based on a normal map baked in Blender. }

These models became the first set that populated my Scale Model Hall. A future post will describe the making of the later models and further changes I made to the originals.Â

References

Ward, C. V. & Hammond, A. S. (2016) Australopithecus and Kin. Nature Education Knowledge 7(3):1